7 Underrated UX Principles

The fields of user experience (UX) and product design are relatively large; in that — if you’re a newcomer to the field and want to study UX design there’s a lot to learn and a great many UX books to be read and courses to be completed. You can install a browser extension like UX Principles to give you constant reminders — but where do you start, and which principles should you focus on?

If only there was a way to ‘shortcut’ this process and learn a few basic UX principles that solve the most common UX problems.

Dear reader, this list is designed to do just that! By the end you’ll have 7 rock-solid ‘golden rules’ to follow. It won’t show you how to become a UX designer, but by building UX patterns to these principles, you’ll make your users happier and deliver the best effort-to-impact ratio for your design decisions.

Here are 7 selected extracts, taken from my 2018 book ‘101 UX Principles’ to help you supercharge your ascent to UX greatness.

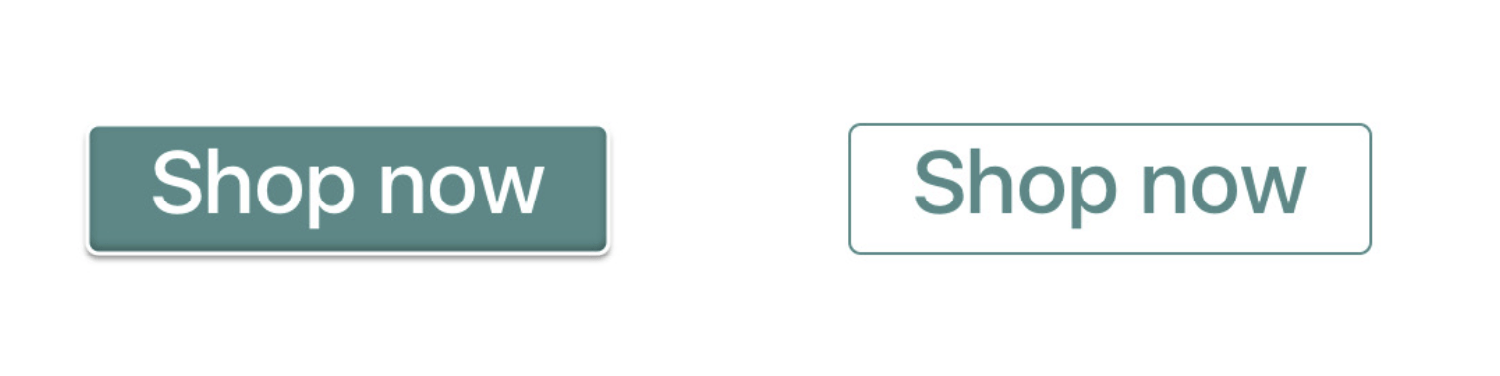

#1 Make buttons look like buttons

This is less of a problem today than it once was, simply because UI frameworks like Bootstrap have a great set of default buttons.

Buttons that exhibit visual affordances (called ‘signifiers’) such as texture and pseudo-3D shadows (left) consistently perform better in user tests than those without them (right).

By drawing on real-world examples, we can make UI buttons that are obvious and instantly familiar. The human visual system is tuned to see depth, and by including the illusion of depth in your UI, you add a whole layer of useful information for the user.

Using real-life inspiration to create affordances, a new user can identify the controls right away. Create the visual cues your user needs to know instantly that they’re looking at a button that can be tapped or clicked.

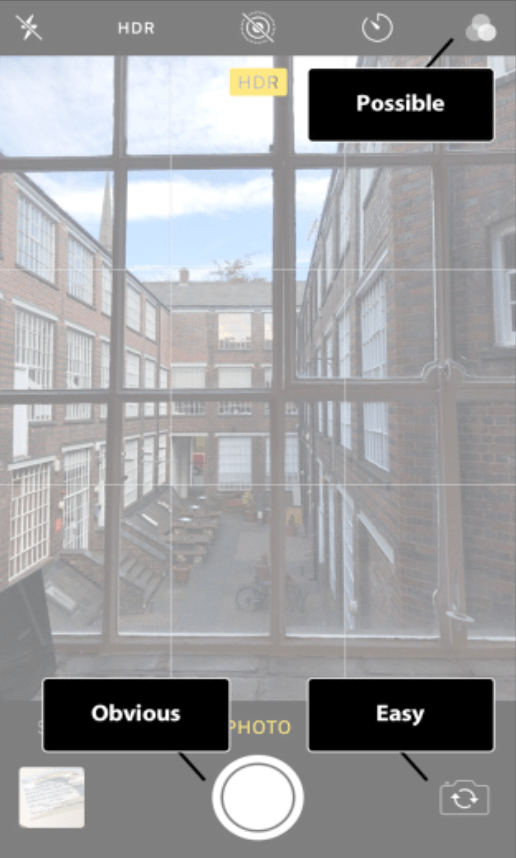

#2 Decide if an interaction should be obvious, easy or possible

While we want to make our products as intuitive and familiar as possible, there will always be ‘advanced’ options and rarely-used features — real life problems are often complex and some software just has to be complex too.

You can decide where a control should be placed, or how an interaction should be designed, by beginning to classify interactions into one of three types;

Obvious: Obvious interactions are the core function of the app, for example, the shutter button on a camera app or the new event button on a calendar app. They’re the functions that users will likely perform every time they use your product and their controls should be visible and intuitive. Hiding these away — either accidentally or intentionally — does still happen and it’s often a cause of massive frustration for users and the failure of new products.

Easy: Easy interactions are the hardest to classify and often we’ll only get these right after several rounds of iteration and user feedback. For example, an easy interaction could be switching between the front-facing and rear-facing lens in a camera app, or editing an existing event in a calendar app. The controls should be easily found, perhaps in a menu or as a secondary-level item in the main controls. They’re the toughest to get right because they’re used too frequently to be tucked away, but they are not used every time, which means designers will often de-prioritize them too heavily.

Possible: Interactions we classify as possible are rarely-used and they are often advanced features. They need to be discoverable, but they shouldn’t be given the same prominence as obvious or easy interactions. For example, it is possible to adjust the white balance or auto-focus on a camera app, or make an event recurring on a calendar app. These advanced controls can be tucked further away, as the majority of users will not need to see their UI cluttered with them.

The iOS camera UI (above) balances these three classes of interaction well.

#3 Hide ‘advanced’ settings from most users

There’s no need to include every possible option in your menu when you can hide advanced settings away. Group settings together, but separate out the more obscure into their own section of ‘power user’ settings, which should be also grouped into sections if there are a lot of them (don’t just throw all the advanced items in at random).

Not only does hiding advanced settings have the effect of reducing the number of items for a user to mentally juggle, it also makes the app appear less daunting, by hiding complex settings from most users.

By picking good defaults (coming up next!), you can ensure that the vast majority of users will never need to alter advanced settings. For the ones that do, an ‘advanced menu’ section is a pretty well-used UX pattern.

#4 Think carefully about your defaults

The power of default settings is often overlooked, but they have huge potential to affect the UX of your product.

Some examples of great defaults:

-

When I get into my car, the default sound output of my phone switches from handset to in-car speaker. I can change it, but the default is sensible.

-

Sign in to an analytics product and the selected date range is ‘this week’, with a comparison date range of ‘last week’ Imagine if the default was ‘today’ and showed no data — useless, right?

-

When I tap a name in my “recent calls” view, my phone calls that person, rather than starting a new text message or video call. Those options are tucked away in a context menu.

Picking a good default is a balance of factors:

-

How many users you think (or know through research) want this default behaviour

-

How difficult it is for the user to change to an alternative

-

How discoverable that alternative setting is

As a professional product designer, it’s your job to weigh up these factors and some of that judgement will be based on ‘gut feeling’, as well as evidence.

There’s a temptation to expose a new feature or functionality — just because it’s new — and make it the default setting. Don’t do this. Your users don’t care about something because it’s new: they care whether it’s useful or not.

How many times have you heard users complain, “They’ve updated the app and now it makes you do X”? If X was an option, rather than the new default, you’d have happier users.

Also, be aware that the vast majority of users don’t venture into settings menus and will simply use a product with its default setup. For the bulk of your users, the default setting is the only setting, so choose well.

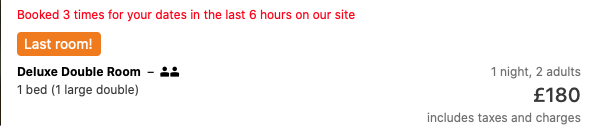

#5 Don’t be evil

Modern apps and mobile games often feature ‘hook cycles’ — patterns of response and reward that aim to draw you in and make you addicted to the product. What’s more, the ‘dark patterns’ found all over the web are well documented and still rising in prevalence.

In some fields, medicine for example, professionals have a code of conduct and ethics that forms the core of the work they do. Building software does not have such a code of conduct, but maybe it should do.

All of these dark patterns and addictive products were designed by normal people working in normal software companies — they had a choice. They chose to fight for the company, not the user. Be a good UX designer and don’t be evil.

A sense of urgency is a frequently-used dark pattern on hotel booking sites.

#6 Test with real users

You need to test with real users, not your colleagues, not your boss and not your partner. You need to test with a diverse mix of people, from the widest section of society you can get access to.

User testing is an essential step to understanding not just your product, but the users you’re testing — what their goals really are, how they want to achieve them, and where your product delivers or falls short. You’ll not only understand your users better, but you’ll reduce development time by short-circuiting the feedback loop and getting problems fixed much earlier in the product life cycle.

It’s never too early to start testing — an unfinished prototype or even paper prototype (cards or post-it notes that you move around on a desk) can yield valuable insights — get your product in front of users as soon as you can.

There’s a myth that user testing is expensive and time-consuming, but the reality is that even very small test groups (less than 10 people) can provide fascinating insights. The nature of such tests is very qualitative and doesn’t lend itself well to quantitative analysis, so you can learn a lot from working with a small sample set of fewer than 10 users.

There’s research (Why you only need to test with 5 users, NNG) to show that testing with as few as five users will uncover 85% of usability problems in a single test.

Test with real users and listen to them, and you’ll build something they love.

#7 Make your product work like all the other products users know

Also known as Jakob’s Law of Internet User Experience, which states:

“Users spend most of their time on other sites. This means that users prefer your site to work the same way as all the other sites they already know”.

Over the years, I’ve found that part of the imagined ‘code of practice’ of designers is to not steal. As we train and learn, we’re taught to develop our own design style and not to borrow too much. Imitation is discouraged and copying the designs of others is frowned upon, dishonest even.

Your users spend the vast majority of their lives not using your product. They spend that time on other sites, other web apps and other mobile apps.

The product with which they’re least familiar is your product.

You should aim to build upon established patterns, for example:

-

Forms that allow simple data entry, easy movement between fields, and a ‘submit’ or ‘save’ button

-

Pages or views in your product that tell users how much the product costs, in total, without hidden fees

-

Obvious controls, links that look like links and buttons that resemble buttons

-

Search that works quickly and shows the most relevant items first

Your users have spent many years using products just like yours, so should your product work just like those other products or radically differently?

The answer is: “just like those other products”.

It’s not exciting or sexy — you’re not inventing a whole new class of product or interface, and you’re not revolutionizing a whole product sector. What you are doing is the good work of a UX professional: building on the established practices that users know and love from years of experience.

Your satisfaction comes not from reinventing the wheel but from giving the user a wheel that they already know how to use. This will give them the tools to get their jobs done and improve their life just a little bit.

More UX Principles?

The totally free UX Principles Browser Extension teaches you a useful UX tip with every new tab you open for Chrome & Firefox, with over 200 UX principles from UX luminaries like Jakob Nielsen, Bruce Tognazzini and Don Norman.

The book 101 UX Principles, is available now in paperback, Kindle and eBook formats.